A Stitch in Time: The ‘Broken Treaties Quilts’ of Gina Adams

Gina Adams’ journey to becoming a political artist began as she probed deeper into her Native roots. Trained as a painter and printmaker, Gina Adams made apolitical art for many years. It was beautiful work that hinted at her cultural heritage, but it didn’t make a statement.

While studying the effects of post-Colonial trauma and assimilation at the University of Kansas, Adams identified feelings of remorse and grief in her own life, stemming from her Ojibwe-Lakota grandfather’s forced boarding at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. Her art began to change.

“I realized how powerful it was to be able to speak about all of those feelings,” said Adams, who lives in Longmont, Colorado. “I started thinking about creating a body of work that could be a signifier, to really speak about the issues I wanted to address in my art work.”

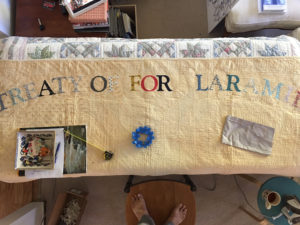

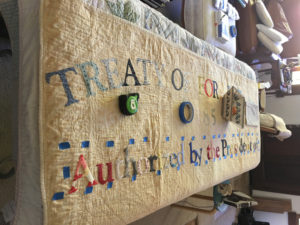

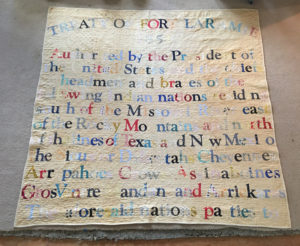

Her latest body of work, “Broken Treaties Quilts,” involves sewing text from Indian treaties onto antique quilts to talk about the ways Indians and their communities have been deceived, violated and marginalized by the U.S. government. Sewing the words of injustice, letter by letter, onto objects of comfort and beauty represents the turmoil that Indians have suffered, and reminds viewers of the relationship between those broken treaties and Indian communities today.

Adams, 52, recently finished quilts about both the 1851 and 1868 Fort Laramie treaties, which she made in response to the Dakota Access Pipeline standoff at Standing Rock. She has made 18 quilts so far, and shown them from Maine to the Midwest. Wherever she shows her work, she makes a new quilt that’s relevant to the treaty history of that geographic area. Her goal is to create a quilt for every U.S. state.

It’s Honor is Here Installation

- Courtesy Gina Adams

There’s no shortage of broken treaties, she said, and all were populated with twisting, confusing language that purposefully misled people and subjected the treaties to misunderstanding and different interpretations.

Adams has spent most of the past three years reading the treaties, word for word. “In cutting up these letters and reading and re-reading these treaties, you begin to realize how the language was meant to be confusing when they were written. They are still confusing today. They’re very duplicitous in their meaning,” she said. “You can understand why the misunderstandings happened.”

The quilts hold to account the perpetrators of the broken treaties, and enable Adams and others who have suffered because of treaty violations to express their own broken history, burden and loss.

“Now I choose to weave that over-arching sadness into a source of tremendous comfort,” she says in her artist statement. “This is my truth; I sew the words, powerful speech, for my people, for my family, and for myself. It is an act of giving back the misuse and abuse of power.”

Adams chose her medium with intentionality. In Native cultures, the quilt transcends modern timekeeping. It’s been around forever, serving as a source of warmth and comfort, as well as a feeling of home and family. Quilting is also thoroughly American, she notes, and both the quilt and quilting bees symbolize community and the idea of working together.

Adams’ “Broken Treaties Quilts” are subversive because they convey aesthetic beauty in the folk-art tradition while representing the letters and words the government used to subject Native communities to generations of pain and instability. They are beautiful in their appearance, impressive in their craftwork and powerful in their political statements.

Adams begins with antique quilts that she finds at flea markets and elsewhere. Many people also give them to her. She prefers quilts that are a century old or older, so they reflect the general vintage of the treaties she represents.

She hand-cuts letters from calico fabric, because calico was the first industrialized commodity made in the United States and exported to Europe. She uses the Goudy Old Style font for letters, because it most closely resembles the fonts of the frontier newspapers that reported on the Plains Indian wars, adding another layer of meaning.

After cutting the letters, she assembles them on the antique quilt, spacing them carefully before ironing them with a dry hot iron. After adhering the letters to both sides of the quilt, she uses a sewing machine to baste the first side, then repeats the process on the other side. She then spends about a week detail stitching the front and the back of the quilt so that each edge of every letter is stitched.

The process of making the quilts is time-consuming and labor intensive, and enjoyable, Adams said.

“It’s very contemplative. It’s very mindful,” she said. “I so look forward to every single aspect of it, even when I am doing the detailed stitching on the quilt. It’s a really focused time. I am lost in my thoughts and just focusing on the work itself. I find it to be so rewarding.”

Adams has been comfortable with a needle and thread since age 7, and her mother gave her a sewing machine for Christmas when she was 8. She began quilting at 11. Adams makes clothes for her son, just as her mother did for her.

“I love fabric. I love soft fabric. I love linens. I am enthralled with color and fiber, and I always have been enthralled by it. Sewing is a part of my creative practice, and I am always collecting scraps and fabric,” she said.

- Courtesy Gina Adams

A visual of Adams organizing the fabrics to be used on the quilt.

Adams’ personal history is deep and layered. She descended from indigenous and colonial Americans. Her grandfather was Ojibwe and Lakota, and Adams has always identified with her Native roots. “I remember being 3 and 4 years old and going on hikes with my grandfather. He would talk to me and introduce me to plants and animals and things in nature in the Ojibwe language,” she said. “He would tell me everything in Ojibwe and then translate it. It was a wonderful connecting point that stuck in my heart and soul and has been there my whole entire life.”

Adams, who is not an enrolled tribal member, plans to take Ojibwe language classes this fall, to deepen her cultural immersion.

Gina Adams graduated from Maine College of Art in Portland, Maine, in 2002, and earned a master’s degree from the University of Kansas in 2013. The “Broken Treaties Quilts” project has enabled her to grow as an artist and an individual. It’s been an evolution, with other projects along the way. But this one feels more significant and lasting.

“I’ve always wanted to say something in my work, and I think I’ve really got something here that has the power to make change,” she said.

The Quilting Process

Gathering quilt and fabric: Gina Adams begins with an antique quilt, preferring those that are a century old or older. She finds them at flea markets and estate sales. The quilt for her first Broken Treaty Quilt came as a gift from her mother, purchased in the summer of 2013 at a flea market in Massachusetts. The night she received the quilt as a gift, Adams dreamed about stitching a broken treaty on the back of the quilt. For the letters, Adams used many varieties of colorful cotton calico.

Organizing fabric and cutting letters: After deciding on the quilt and fabric, Adams cuts the fabric into small rectangles, numbering each and placing them on the antique quilt based on the interplay of colors. “I place them in an order where the color is speaking or relating to each other,” she said. From each piece of fabric, she hand-cuts the letters of the treaty, using a Mylar stencil. Each lowercase letter is about 4 inches high. She uses Goudy Old Style, which most closely resembles the fonts of frontier newspapers that reported on the Indian Wars.

Courtesy Gina Adams

Placing the letters: It took Adams nine months to cut the letters for her first quilt. Now she can cut the letters in two to three weeks. After cutting the letters, she places them on the surface of the antique quilt. She starts with the title of the treaty on the back of the quilt, carefully measuring and placing each letter. She irons the letters with a dry hot iron, filling both sides of the quilt with words and letters. After each side of the quilt is adhered, she uses a sewing machine to baste one side, then the other.

Quilt assembled: After the letters are placed and the quilt basted, Adams spends about a week detail stitching so the edges of every letter are firmly secured, front and back. It takes about six weeks to make a quilt. She has made 18, and decides which treaty to make based on the geographic location of her upcoming exhibitions. She wants to make one for each state and Canadian province. Their sizes vary. No two are the same.